Clik here to view.

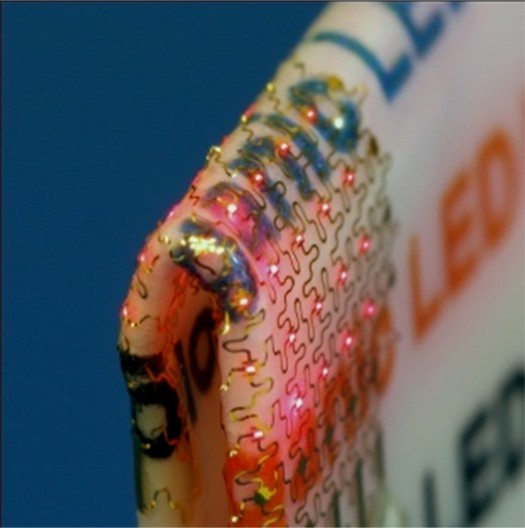

“U Illinois arrays, by contrast, use the traditional semiconductor gallium arsenide (GaAs) and conventional metals for diodes and detectors.” — Coxworth, Ben. Flexible, Biocompatible LEDs Could Light the Way for next Gen Biomedicine. Gizmag, 22 Oct. 2010. Web. 28 Mar. 2014.

“How can you believe in God and science at the same time?”

Even though I am rarely asked this question so plainly, it is often implied in conversation. Many atheistic advocates think that there is a conflict between the two. They may suspect that a belief in the supernatural is used primarily to explain the physical world with non-physical means and to “fill in the gaps” for conundrums for which there is no better or more reasonable determination. They may believe that beliefs are driven by a search for meaning and cohesion, and that this persistent pursuit of Reasons may mistakenly (and somewhat ironically) lead people to become more irrational. They may believe that science, as the ultimate paradigm in methodically inductive, deductive, and reductive Reasoning, is consequently the most obvious arbiter of truth. They may then believe that the willful denial and rejection of conclusions arrived at by science is therefore illogical, irrational, and subsequently idiotic. It is therefore reasonable to see why people would automatically consider those who believe in the supernatural to be willfully ignorant, regarding them with suspicion, condescension, and/or frustration.

I grew up saturated in both religion and science. My father is an electrical engineer, well accomplished and respected in his field. As a child, I was surrounded by gizmos and textbooks, not understanding what “GaAs Semiconductors” were but curious to find out. His approach to the world has always had the paradigm of a scientist: always thinking, observing, and making his own private conclusions. He had a very strong moral sense, but it was strongly grounded in a Confucian sense of discipline, orderliness, and character virtue. He was not a Christian at the time and he generally took an agnostic and aloof stance towards religion, seeing it as a generally positive force in shaping his family’s sensibilities but still regarding it cautiously. It was almost as if he was wary towards the existence and significance of a God who seemed to be a relatively benign but otherwise untested hypothesis.

My mother is a firm Christian and a nurse, nearly opposite to my father in temperament and belief. Where he is cool and detached, she has been deeply suffused with emotion. Where he sought out natural principles and laws of order in the physical world, society, and human relationships, she has been attuned to spiritual precepts and looks to them as Reasons why things are what they are. She is diligent and meticulous in this way, always keeping an eye out for them, an ear cocked for the whisper of a consequence or a lesson. Most were simple illustrations and object lessons of basic character: an irritating person was placed in my life to teach me patience; a flat tire the day after a stingy financial decision was a reminder to be more generous; an unexpected piece of good news was an example of God’s consistent goodness. Some links were easy to see and understand. Others were not.

I grew up listening to both these narratives, never really seeing a conflict between the two paradigms. They are both internally consistent in their logic. They are both meticulous in assessment and constantly rework the available evidence into a deterministic and causal understanding of the world. I had been taught that, though science could inform much of the “how” of life, only religion could provide the “why” with any degree of functional certainty. I supposed it was the way in which everyone learned to make sense of an otherwise haphazard world, how we maintained the hope to cope through difficult situations. But as I grew older, reason began to challenge the Reasons.

It started with the big questions. Were people really poor because they were lazy? Was HIV really God’s punishment to homosexuals? Was evolution really at odds with Christianity? And of course, the biggest of them all: is there a Reason for suffering?

Clik here to view.

Hungry

For nearly each of these questions, I had trouble accepting the answers from my mother. We would go through endless cycles of arguments, some of which were very heated and charged with bitter words. Sometimes I held on to prove a point, but I often found myself fighting out of sheer stubbornness and pride. I was challenging the Reasons because I began to doubt that there were any. I was not certain that any amount of goodness truly governed the natural world, and strongly suspected that humanity was alone in its struggle to survive sentiently. This breakdown in faith in the divine, which began in college, blossomed in medical school.

Madness and chaos. That was what disease seemed to me, the struggle between life and death in the hospital wards. Kind and generous patients suffered from horrific fates while those who were malingering and malicious fed off of the system’s generosity without punishment. The hospital was a new and disorienting place in which the old rules, the old Reasons (either physical or spiritual) no longer seemed to apply. Who lived and who died was less a function of morality as it was of biological processes, state variables, and lots of luck. In a world where so much was at stake, only the new reasons, the Evidence of hard data and tight correlations mattered. And yet even there, the most basic assumptions about standards of care were challenged and occasionally overthrown by the latest and greatest studies, and many reasonable, long-standing associations between health and disease once thought to be clinically objective disintegrated under closer scrutiny.

My own shift in perspective was subtle at first, and I wasn’t able to articulate my discomfort with it until one of my friends began using “evidence based arguments” for everything. He would launch into a political discussion with others and pepper them with the question, “Where’s your reference? Show me the study.” It was an irritating thing for him to do in the context of otherwise casual conversation, but the inflammatory nature came from the realization that most of what we say on a daily basis is completely speculative. We make conclusions based on very little evidence because that is how we must deal with the complexities of daily life, but if we truly realized how uneducated and sporadic those decisions were, we would lose the confidence to make it from one moment to the next.

Something in me hardened. My faith in God, the Ultimate Reason, which had once been so strong began to settle for lesser things. God may count the hairs on your head, but I can tell you now that it will be exactly zero once your chemotherapy is started. You can pray for a miracle, but if we don’t amputate that leg tomorrow you might lose your life. Praying is good, but praying 20 hours outside in the snow is not; please restart your bipolar medications or we won’t let you out.

And so prayer, something I once loved to do, became more an act of desperation and a superstition than one of faith. I didn’t know what to pray for, mainly because I was tired of being disappointed. I began knocking on wood and crossing my fingers because they seemed to be just as effective: barely, if at all. I was tired of BS and really just wanted to admit: I don’t know I don’t know I don’t know.

Clik here to view.

Tissot, James Jacques Joseph, 1836-1902. Tower of Siloam, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=55003 (retrieved March 28, 2014). Original source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_The_Tower_of_Siloam_(Le_tour_de_Silo%C3%AB)_-_James_Tissot.jpg.

Finally, at the end of a long year in clinical rotations, a collapsed lung (pneumothorax) knocked me out long enough to mull it over in my mind. True to form, my mother insisted that there was a Reason behind my lung collapse, that the timing, the method, the stresses I was going through were all too coincidental to be due to anything else. And we talked, perhaps for the first time, about what it meant to use reasons and to look for Reasons. It reminded me of the Tower of Siloam:

There were some present at that very time who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. And he answered them, “Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. Or those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who lived in Jerusalem? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.” — Luke 13

Whenever I talk at length about the nature of suffering, I mention an example a mentor once used. Suffering is just the push that tips a cup over; it has no bearing on what comes out. This is what I have come to believe about suffering, illness, death, and all Events with consequences for which we seek a Reason: they reveal what is inside me, deep down inside that refuses to come out otherwise. I may have no control over my environment or the insanity of this small earth we inhabit, but there is always something in me that I can ask to have transformed:

Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect. — Romans 12

It made me reconsider epistemology, or the study of how we know anything to be true at all. It made me wonder why I should remain decidedly Christian.

[To be continued…]

Clik here to view.

Rosette Nebula